Projects

The development of the interplay of verbal and facial information in emotion categorization

In this project we study how children develop the ability to combine information from faces and words to perceive emotions. More specifically, we study how the emotional categories of faces and words (whether they are positive or negative), influence the ability of children and adults to correctly classify them. As part of our experiments we use behavioral methods which tells us how quickly and efficiently participants can classify emotional information, as well as eye-tracking, which can tell us how participants visually scan pictures and videos of faces. Thus far, we have discovered that children initially process positive words and faces more efficiently than negative ones, and gradually increase their efficiency of processing negative information as they grow up. We also found that accompanying words have a stronger influence on the classification of faces than accompanying faces have on the classification of words. Currently, were are also investigating the above factors in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Developmental Language Disorder, in order to determine how these conditions can influence the development of emotion perception.

This project is carried out in collaboration with the laboratory of Prof. Dr. Christina Kauschke at the University of Marburg.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

Emotional categorization and crawling

Dr. Michael Vesker and M.Sc. Gloria Gehb

Existing studies have shown that infants can distinguish happy faces from sad or anxious faces as early as 5 months of age. However, the extent to which an emotional facial expression needs to be pronounced in order for babies to see it as a positive or negative has not yet been sufficiently investigated. In one study, 7-month-old infants were able to distinguish a face that was 60% anxious and 40% happy from a 100% happy face. However, the question remains whether this ability is influenced by other skills such as crawling or walking. As soon as babies start to move independently, the interaction patterns of parents with their children changes. Once babies can move on their own to objects that may be fragile or dangerous, parents might show negative emotions, such as fear or anger, more frequently.

Thus, crawling or walking infants are more often confronted with negative emotions than infants who cannot yet move independently. For this reason, the current study will investigate whether infants who are already able to move independently are more sensitive to changes in emotional facial expressions than infants of the same age who cannot yet crawl or walk.

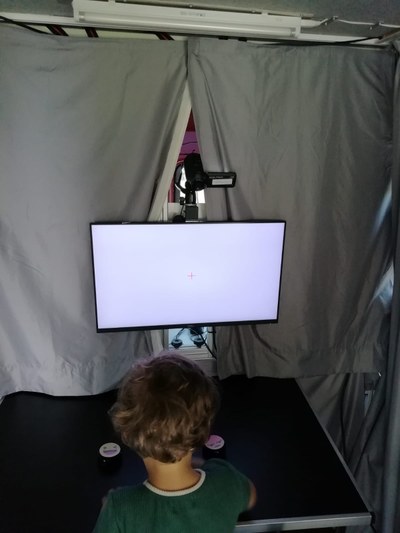

In order to answer this question, the infants in our study are presented with a pair of faces in which one is 100% happy and the other contains a certain percentage of negative emotions. With the help of an eye tracker (a device that records the eye movements), we can then determine whether infants can tell the two faces apart.

Since this study is still ongoing, we still depend on the active support of parents with infants ranging from 9 to 10 months old as well as 12 to 13 months old.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

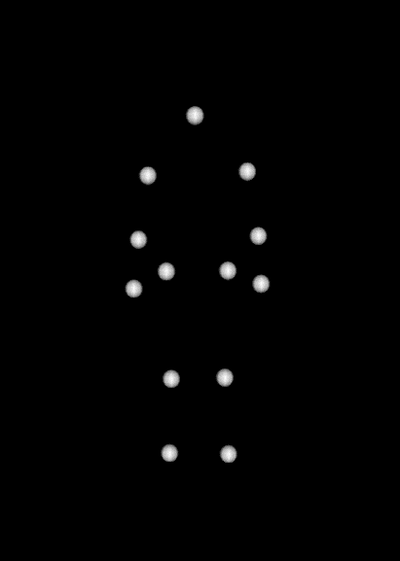

How children recognize emotions from body movements

Just as with faces, we can reliably recognize different emotions from the posture and body language of other people. Particularly in situations with limited sight of other people's faces, for example at dusk, in crowds or at greater distances, we can recognize their emotions and intentions from body movements. It is also known that the recognition of emotions from faces in adults is influenced by posture. Adults evaluate the same face differently depending on the body language of the person shown. It is also known that we can still recognize body movements even when we see very little of the actual person. So-called point-light displays show light points that are attached to the joints of persons. They no longer contain structural information, such as body contours, but still contain movement information. Just a few days after birth, children look at such human representations longer than at a random arrangement of points. At the age of 3 years, children can recognize the actions of people in point-light displays and at 5 years, children are almost as good at recognizing them as adults. In our department we are interested in when emotion recognition develops from body movements in children. In particular, we are investigating the role of interactions between two persons for the recognition of emotions. For this purpose we show children point-light displays of two interacting persons and compare the reaction of the children with representations of only one person. To record unconscious emotion recognition, we use a surface electromyogram to record small muscle activities in the face. An activity in the cheek muscles is shown, for example, when a child smiles and can be observed as a reaction to a cheerful video. Furthermore, we are interested in how emotion recognition from body movements is related to speech development, empathy and social competence.

This study is funded by the IRTG 1901 „The Brain in Action“ of the DFG.

Example point light display

Perception and Action

Perception and action, though usually regarded as separate systems, are deeply entwined. Even the most elementary action, like grasping an object, requires a perceptual analysis, such as, for example, of the object’s position in space, in order to be successful. Exactly how this interplay between perception and action develops, that is, how infants and children manage to coordinate perception and action, is one of our central research questions.

Another important issue motivating our research is the development of action planning. Here, we are especially interested in the development of infants’ ability for anticipatory grasp adaptation to different object features like orientation or size. Moreover, we look at the development of toddlers’ and children’s anticipatory adaptation to task demands arising in the context of multi-step actions. One example of such adaptation seen in adults is the end-state comfort effect: when grasping objects, adults adapt their initial hand orientation to insure a comfortable posture at the end position, accepting an uncomfortable orientation at the beginning. The aim of our current research is to better understand the developmental course of efficient grasping and its underlying factors.

Last, but not least, a significant number of our studies has concentrated on issues of action perception. From birth, babies are surrounded by a wealth of social information. Our principal research question in this context has been, when infants begin to regard the actions they see as goal-directed and, which cues can help them understand the underlying structure of people’ s actions.

Predictive grasping and manual exploration

Based on existing study results, it is already known that babies are able to look at the location where an object reappears within the first half of the first year of life, which moved behind another object and was thus temporarily covered. They can therefore predict (guess) where the object will be visible again. However, it has also been shown that it is much more difficult for infants to reach for the location of reappearance, even predictively. Only at about 8 months of age do infants reach for the location of reappearance at the right time and thus succeed in holding on to a ball that has rolled behind the sofa, for example. However, there have not yet been any studies on how the grasping behavior of infants behaves when an object does not move in a straight line and over the horizontal axis. It is also unclear whether correlations with other abilities, such as exploratory behavior with the hands, affect the ability of predictive grasping. It has already been shown that infants who explore toys a lot with their hands (e.g. turning, palpating or passing from one hand to the other) are better at looking predictively at the place where an object will reappear than infants who rarely do so. For this reason, we investigated how individual manual exploratory actions affect the predictive grasping behavior.

In one task, the infants saw how a large and a small sphere were alternately covered and uncovered as they moved up and down along a circular path. The babies had the possibility to reach for these balls. The second task was to record the manual exploration behavior. Here the babies were offered 5 age-appropriate toys in turn for a certain time and could play with them as they liked.

It turned out that infants who frequently scanned the surfaces and edges of a toy with their fingers also had a higher prediction rate in the predictive grasping task. Thus, the infants started to initiate their grasp at the right time. Dealing with objects by scanning their surfaces and edges seems to have a positive influence on the general understanding of object properties, e.g. their arrangement in space.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

Examples for the toys

Example for the set-up

How material properties influence grasping movements

Without ever having touched an object in advance, we are able to estimate how heavy an object is, how smooth or rough it feels and how soft or rigid its surface is. We have a vivid imagination of material deformability and how various surfaces appear in different shapes and lighting. Identifying different material properties correctly helps us to decide whether an edge is sharp, how ripe an apple is or how creamy and hot a soup is. All of this material information makes it easier for us to control our body movements when we get in contact with the object. For example, we know how many fingers we need to grasp an object efficiently or how powerful our grasp should be. Only with the knowledge of the material information we succeed in grasping without squashing or dropping the object. In our experiments, we investigate how infants perceive and recognize different object properties and how they use them for the execution of an appropriate grasping movement. We are interested in the impact of visual and haptic information about material properties and how infants use these hints to adjust their prehension movements in anticipation. Furthermore, we examine hand kinematics, like acceleration, speed and hand aperture in the relative timing of the grasping movement.

Schematic representation of the experimental set-up

Illustration of the object used in the study

Gaze behavior and crawling

M.Sc. Amanda Kelch und M.Sc. Gloria Gehb

Some studies have already dealt with the relation between crawling and performance in search tasks in infancy. Other studies have also examined where babies look while crawling. These studies showed that babies who have been able to crawl for a long time performed better in search tasks than babies of the same age with little or no crawling experience. However, it has not yet been investigated whether infants with and without crawling experiences differ in their search performance when they were familiarized with a room in the same way and in the same position. Furthermore, the question remains open whether infants with and without crawling experiences differ in their gaze behavior when they are introduced to a new room.

To answer these questions, in the current study, infants are pushed in a baby walker through a room with various attractive objects and are allowed to look at them as they wish. Then things in the room are changed and the babies are pushed through the room again. A mobile eye tracker (a headband with a kind of camera attached to it) is used to record where the babies are looking at.

As this study is still ongoing, we are looking for participants aged 9 to 10 months.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

Experimental setup

Perception and Processing of Sizes in Infancy

Within the International Research Training Group (IRTG) 1901 “The Brain in Action”, funded by the DFG, we are investigating when and under which circumstances infants exhibit knowledge of the familiar size of objects. When we talk about familiar size, we mean the typical size an object has.

Infants are confronted with objects of different sizes on a daily basis. They are surounded by toys that are much smaller or larger than their familiar-sized real-world counterparts. A dollhouse e.g. is a scale model for a real-world house. As adults, when we encounter an apple the size of a watermelon, we would be puzzled. Infants, however, might not be puzzled about the watermelon-sized apple as they first have to learn the familiar sizes of various things.

In our daily lives, however, we not only encounter real objects, but also pictorial representations of objects. On pictures, the sizes of objects can differ even more from their familiar sizes. In a picture book, the picture of a cat can be rendered the same size as the picture of a tiger. Past studies have shown that adults demonstrate knowledge of the familiar size of objects, when presented with real objects as well as pictures. In our current project, we investigate when and under which circumstances infants exhibit knowledge of the familiar size of common objects. Herefore, we present 7- to 15-month-old infants sippy cups and pacifiers in their familiar size and novel sizes as real objects and pictures of those.

This project is carried out in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Jody Culham from the Department of Psychology and the Brain and Mind Institute at Western University, London, On, Canada.

This study is funded by the IRTG 1901 „The Brain in Action“ of the DFG.

Example of the objects used in three different sizes: the mini, the known and the maxi size (front to back)

Example of how the experiment works: the baby sees the photo of the drinking bottle in maxi size (left) and known size (right)

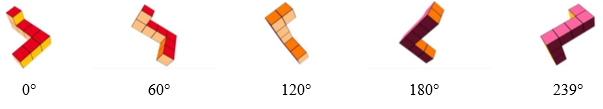

Mental rotation and action experiences

Mental rotation describes our ability to rotate an object that we see in our minds. This is an important spatial-cognitive skill even for babies and allows them to recognize a particular object when different views of it are presented to them.

Past studies from our group were aimed at determining if and when babies are capable of such mental rotation processes. We were particularly interested in determining if there are specific factors that facilitate the acquisition of the skill. Results from these studies showed that motor actions such as the ability to move about independently or to manually explore objects in a sophistictaed manner promote infants‘ mental rotation ability.

In our current project we now want to take a closer look at this beneficial relationship between motor actions and mental rotation ability in infants. We ask whether infants with more advanced motor skills are better in perceiving and utilizing self-induced spatial information from their surrounding when mentally rotating objects.

left: Example of a rotation object, right: the babies are allowed to rotate these cylinders and receive rotation-relevant and -irrelevant information

In a second study about mental rotation, we want to investigate if the way infants explore objects impacts their ability to mentally rotate objects. In this study infants can explore the object (see picture) with a specific procedure (e.g. rotating it or scan the surface with their fingers) prior to the mental rotation task. In this case we are interested, if the quality of exploration, that means the way they explore an object, is relevant for recognizing objects from different perspectives.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

The baby explores the rotation object with its hands

Mental Rotation and Locomotion training

Previous studies have already investigated the relation between crawling and mental rotation in 9-month-old infants. These studies showed that infants who had been able to crawl for a long time performed better in mental rotation than same-aged infants with little or no crawling experience. However, it is still unclear which factors of crawling influence this ability to perform mental rotation. For this reason, 7-month-old infants without any crawling experience were trained in their locomotion. One group was able to move independently with the help of a baby walker. The other group also sat in the walker, but was pushed around the room. The babies had the possibility to get the same visual impressions, but only one group had the possibility to get self-induced locomotion experiences. A third group received no training at all and only completed the task of mental rotation. Before the three-week training period began, the infants were tested in their mental rotation ability and after the training period a second time to detect changes.

It was found that the infants who were able to move in a self-induced way during the training period showed a better mental rotation performance after the training period than before. However, the group that was only pushed through the room and the group that received no training did not change in their mental rotation performance. It can therefore be assumed that the interaction of visual and motoric locomotion experiences has a positive influence on the mental rotation performance.

The study is funded by the SFB/TRR 135 of the DFG.

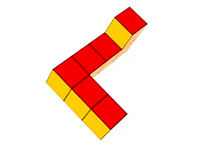

Example of the rotation of the object in the mental rotation task

Example of our circuit

2D/3D-Perception

Within the framework of the International Research Training Group “The Brain in Action”, we are interested in answering the following questions: Are infants able to understand the difference between a real object (3D) and its two-dimensional counterpart (2D)? Is this understanding innate to human object recognition or is it learned by successful attempts to interact with real objects, and failed interactions with depicted objects? Being an adult, it seems to be quite easy to tell the difference between a real object and its corresponding 2D object. For example, we would never try to drink out of a depicted coffee cup. However, it is still unclear, when and especially how infants acquirethis kind of understanding. To provide new insights into the development of infants` 2D-3D perception abilities, a series of studies will be carried out in close collaboration with the Canadian research group of Prof. Dr. Jody Culham, addressing the questions mentioned above.

Collaborators: Dr. Jacqueline C. Snow, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

Clubfoot

In this project, we are interested in the development of children with congenital idiopathic clubfoot. We are particularly interested in the development of spatial-cognitive, language, gross and fine motor skills in the first years of life. Another important issue motivating our research is the social and emotional development. Additionally, we address the question how the parents deal with the impairment of their children.

Collaborators:

Dr. med. Christian-Dominik Peterlein, Mühlenkreiskliniken Bay Oeynhausen

Dr. med. Ute Brückner,Klinik für Kinderchirurgie und -urologie Klinikum Bremen-Mitte

MoViE

The aim of this project is to investigate the development of motor, spatial cognitive and perceptional skills of children with congenital strabismus/esotropia. Additionally, we are interested in their social and familial development and the effects of late surgical correction of strabismus.

Collaborators:

Prof. Dr. Birgit Lorenz, Augenklinik der Universitätsklinik Gießen.

Music and Cognition

Does making music make you smart?

This is exactly what we are investigating in our current projects.

Do music lessons enhance intelligence in primary school children?

Some studies indicate that children who take music lessons achieve better results in intelligence tests than children who do not take music lessons. However, it is still unclear whether smarter children are more likely to learn an instrument or whether music lessons influence cognitive performance. There are very few high-quality studies yet suggesting that music lessons can cause an improvement in the? performance of? an intelligence test. Therefore, in a current study, we would like to investigate whether learning an instrument enhances intelligence in primary school children and whether comparable leisure activities, such as drawing, show a similar effect.

What mediates the relationship between music lessons and intelligence?

Some studies have shown a positive correlation between music lessons and intelligence. Our aim is to investigate this relationship more in depth. We have shown that, for example, so-called executive functions* (e.g. planning, selective attention, inhibition and cognitive flexibility) can explain part of this relationship. In our current projects, we are investigating the relationship between music lessons, executive functions and intelligence across different age groups. We are also interested in whether there are other mediating variables besides executive functions.

Do music lessons enhance executive functions in childhood?

Previous studies have shown positive associations between music lessons and various executive functions such as selective attention, working memory, inhibitory control or cognitive flexibility. However, there is still a lack of studies that provide evidence for the positive influence of music lessons on executive functions. Current research in our department suggests that making music in childhood can enhance executive functions Based on this, we are now interested in whether different musical activities such as singing, dancing or rhythm training influence executive functions in different ways. First results show that rhythm training compared to singing training or sports training enhances motoric inhibition in pre-school children. In upcoming studies, we would like to investigate these findings more in depth.

*Executive functions are general cognitive abilities that we need in order to control our attention and to concentrate. They enable us to think and act in a goal-oriented manner.

This project is funded by a grant of the DFG.